Race Still Matters: Reflections on a new tool centering student voice, equity and systemic change

by Dominique Horton and Mackenzie Hahn

Squeezing in a bite to eat before the bell rings and putting the finishing touches on his plans for the rest of the day, a teacher prepares to welcome his students back to the classroom on a typical Florida August afternoon. While trying to gather his thoughts in preparation for the next lesson, a staff member stopping by his classroom notices his bright and colorful bulletin board of African American heroes. The staff member confronts the teacher, stating that the images are “age inappropriate”. They exchange words while the staff member removes them and walks out the door continuing their rotations around the school building.

The teacher feels shocked, rattled and defeated, but the bell has rung and students are finally filing back into the classroom with the help of a dedicated classroom aide. As he attempts to rein in excitable students, a student whose desk sits near the once colorful area asks, “Mr. James, what happened to the bulletin board?”

While we don’t know if this is exactly how this all went down earlier this month, what we can imagine are the frustrated feelings of a teacher in a majority Black school desiring only to motivate his students with images of exceptional African American leaders. I wonder what messages his students internalized when those leaders who looked like them – Martin Luther King, Harriett Tubman, Colin Powell, George Washington Carver and former President Obama were deemed “inappropriate.”

The last two years in education have been, well, a whirlwind. Some have even said American schools are in crisis. Pummeled by the complexities of the pandemic particularly around vaccines and masks, schools nationwide are now grappling with an already increasing teacher shortage. Added to these challenges are those of continued controversies over curriculum and race.

I, Dominique, a former school social worker well acquainted with a typical school day and Mackenzie, the daughter of a long-time educator and administrator familiar with the toll these challenges and others have on the life of a teacher leader, grappled with the Florida incident. How did those students feel when the tribute to their heroes was removed from their classroom?

Student voice is critical in constructing the policies and practices that impact their daily lives. Education professionals may believe that they understand their students’ experience, but there is no way to correctly understand each student’s reality without asking every student. Highlight was created to bridge the gap between the people that work in schools and the students that learn in schools in order to create a better understanding of the lived realities of the least consulted demographic: students.

What is Highlight?

Highlight was born from the idea that student voices matter when it comes to what happens in their schools and the opportunity to leverage their creativity as problems arise. Highlight is a tool that gives students a voice to share their experiences in their learning environment by assessing student’s perceptions of five key conditions: Basic Needs, Belonging, Self-Efficacy, Rigor, Hope.

Here are the ways in which Highlight defines these terms:

Basic Needs: Basic needs must be satisfied before higher order needs can be reached (Maslow, 1943; Research History, n.d)

Belonging: Belonging means acceptance as a member or part (Goodnow, 1993)

Self-Efficacy: Whether a person believes in their ability to succeed in specific situations or complete a given task (Bandura, 1977; P2O, n.d.)

Rigor: Access to grade-level standards and instruction that is relevant to the real world, and engaging and responsive to each individual student (TNTP, 2018)

Hope: The perceived aptitude that you can achieve your goals (Snyder et al., 2002)

The five conditions were identified after careful research and development including foundational educational research (Maslow, Bandura, Hope Index), contemporary research (NTP), and developers’ experience leading student advocacy efforts in K-12 school systems. In addition to significant research, the survey underwent an initial pilot testing phase as well as statistical analyses to improve the design of the instrument. An easy to use dashboard was then developed to help schools visualize their data, identify interventions to close conditions gaps and journey down the path of creating a more equitable school experience for all students.

Who is using Highlight?

More than 20 different school campuses and nearly 2,000 students across California and Indiana, spanning students in 3rd through 12th grade, have used Highlight. Multiple schools surveyed their students semesterly. The participating schools differed in their academic models, including seat-based, homeschool, Montessori, project-based, workforce training, and were located in different regions. Of the participating schools, 100% reported value in the Conditions Gap Framework approach; 100% reported interest in re-administering survey; and 100% stated a commitment to developing and aligning equity based interventions with the Conditions Gap Framework.

Looking Forward

Highlight will continue to evolve and grow as more schools use it throughout the country. We have evaluated the collective data from schools that have participated so far and analyzed the total experience of students in California and Indiana. The following is a high level summary of the initial data analyzed and kicks off a series of blog posts that dig deeper into understanding the lives of students nationwide.

Our Top 5 Insights on Student Experience

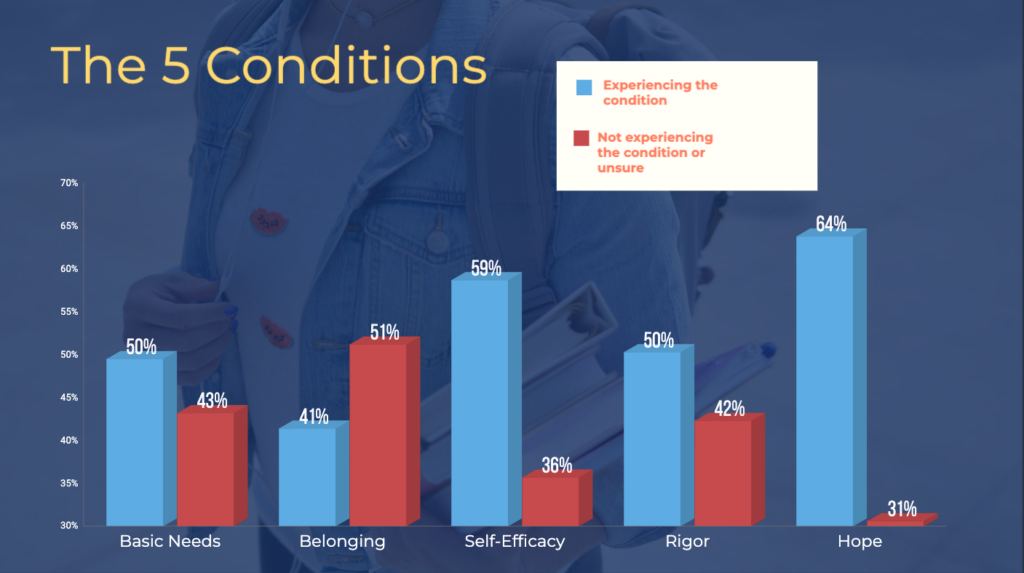

1. Students say they struggle with having their basic needs met, feel as though they don’t belong, and lack rigorous instruction.

Belonging. A strong sense of belonging is shown to be strongly related to academic motivation, and additionally mildly related to improved grades and teacher perceptions of student effort (Walton, 2007). We explored students’ perceptions of belonging at school through statements such as, “I feel welcomed at my school,” “My family’s culture is celebrated at my school” or “My teachers ask me about my interests.” Less than half (41.4%) of the students surveyed indicated feeling a sense of belonging in their school while over half (51.2%) reported feeling as though they did not belong or were unsure whether they felt a sense of belonging to their school community.

Basic Needs. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, a framework originally crafted by Indigenous peoples (Bear et al., 2022), asserts basic needs must be satisfied before higher order needs can be reached (Maslow, 1943). Yet, only about half (49.5%) of students surveyed reported that their basic needs were being met. Students were asked to rate statements such as, “My school is clean,” “My school gives me enough food to feel satisfied” or “I have a school staff member that I talk to when I have a problem.”

Rigorous instruction. Students were also asked questions around rigor through statements such as “My teachers assign me challenging work,” “My teachers have high expectations for me” or “My assignments expand my thinking about the real world.” Again, only about half of students (50.3%) surveyed indicated receiving rigorous instruction. Out of the five questions assessing students’ perceptions of rigor, more students disagreed or were unsure that their assignments expanded their thinking about the real world (39%), that they received challenging assignments (32%) or that they were regularly asked to explain their thinking about complicated tasks (32%).

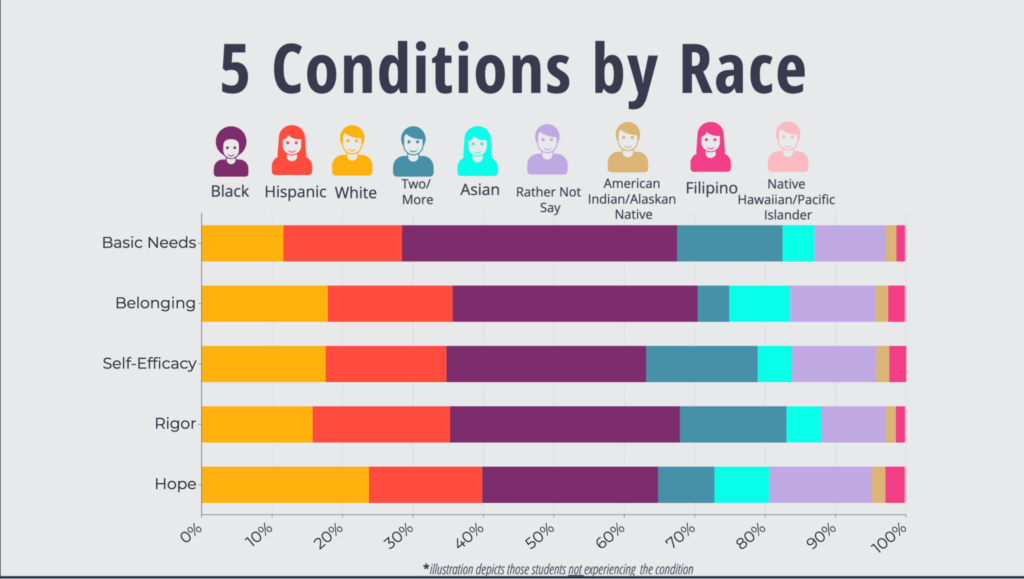

2. Black students were disproportionately represented amongst those students with negative experiences within much of the conditions.

When examining the five conditions by race, we found a statistically significant relationship between race and each of the five conditions1. Black or African American students made up the largest share of those students indicating they did not perceive their basic needs were being met (39%), did not feel a sense of belonging (31%) or self-efficacy (28%) at school nor were experiencing rigorous instruction (33%). Only about 38%, respectively, of Black or African American students reported that their basic needs were being met or felt a sense of belonging, while over half of the Black students surveyed (in both categories) indicated they did not feel a sense of belonging nor did they feel as though their basic needs were being met at school.

Hispanic and Latino/a/x students made up the second largest share of students identifying as not having their basic needs met by the school and not experiencing rigorous instruction. Students identifying as “Two or More Races” made up the second largest percentage of students who did not feel a sense of belonging.

1To explore whether the disproportionality in the conditions was not due to Black or African Americans being the largest population in the sample, a Chi Square Test of Independence was conducted to explore the association between race and each of the five conditions. The results indicated a statistically significant association between race and each of the five conditions (p<.001).

3. Black students say they do not feel safe and their school isn’t clean.

We wanted to know more about why this disproportionality existed amongst the conditions. Basic needs and belonging were especially salient. What exactly was making Black students feel as though their needs were not being met? In examining basic needs condition gap by question, we found that the statements, “My school is clean” and “This is a safe space to attend school” yielded the two largest amount of lowest scores on the Likert scale for perceptions of basic needs. The third statement yielding the largest amount of lowest scores was, “My school gives me enough food to feel satisfied”. Many Black children and adolescents develop in communities that are disproportionately affected by community violence and exposure to trauma (Nebbitt et al., 2020). Additionally, while schools receive federal funds to help equalize the undersupply of property tax funding in low-income areas, these schools, which are many times majority minority, are more likely to have leaky roofs, inadequate plumbing and heating, problems with lighting, inadequate ventilation, and acoustical deficiencies (Evans, 2004). Research has shown that these factors significantly impact academic and social-emotional outcomes for students (Whipple et al., 2010).

4. Many Black students say they do not feel welcomed or as though their opinion matters at their school.

The statements, “I feel welcomed in my school” and “My opinion matters at my school” yielded the largest amount of lowest scores on the Likert scale for sense of belonging. The third statement yielding the largest amount of lowest scores in this category was, “My teachers ask me about my interests”. Research indicates that Black adolescents especially are at heightened risk of belonging vulnerability through education and school policies and practices. These practices can include how they are taught, the type of feedback they receive, the assignments they work on and the disciplinary practices they are subject to and experience (Gray, Hope & Bird, 2020).

5. The good news is, many students are hopeful.

When considering all the students surveyed, 63% of students reported feeling a sense of hope! Hope, compared to any other condition, yielded the highest percentage of students indicating a more positive experience. Hopeful students are optimistic and can visualize their long-term aspirations of who they can become and what they can achieve. When examining across racial categories, Black students made up the largest share (68%) of students who indicated a sense of hope. This included sentiments such as “I am certain I will reach my goals,” “I am excited about my future” or “I have an exciting goal that I am working towards this year.” This isn’t surprising. Research shows that cultural strengths such as positive outlook, spirituality, religiosity, compassion, attitude, social intelligences, meaning-making and others are all persevering processes that African Americans utilize in the face of adversity (Mattis, 2016).

Get to Know the Scholars Who Participated

After administering Highlight to over 20 schools, we were able to analyze a little over 6,300 student responses (n=6,394) regarding their perceptions of the condition gaps. Students primarily attended schools in Indiana (n=2,581 or 49.4%) or California (n=2641 or 50.6%). Our students were majority male (49%) with female students (44%) following close behind. We had a small sample of 61 gender non-conforming students (1%) and those that would rather not share their gender identity (2.3%). The student sample was majority minority. African American (27.6%), Hispanic or Latina/o/x (20.2%) and White students (18.3%) made up the majority of student respondents.

Many of the students surveyed were middle (34.3%) and high schoolers (32.9%) with a little over thirty percent being third, fourth and fifth graders (31.8%). The majority of the students surveyed spoke English as their first language (83.4%) with a small percentage (16.6%) of students who were non-native English speakers. The parent educational backgrounds of the students surveyed were almost evenly distributed between those parents or guardians who had a high school diploma or some college (41%) and those who had earned a college degree or advanced college degree (37%). About 15% of parents or guardians did not finish high school and about 21% of students weren’t sure of their parents’ education level. Well over half of the students who participated have been at their respective schools for at least three years or more and are likely well acquainted with their school environment. Using a 5 point Likert scale with answers ranging from from strongly disagree to strongly agree, students indicated their perceptions of the five conditions as it relates to their school environment.

An Opportunity

Highlight by Friday offers school districts, schools and administrations the opportunity to walk towards authentic educational justice and improved academic and social-emotional outcomes for all of their students by centering student voices. Dawn McConnell, Chief Operations Officer of John Muir Charter Schools, has and continues to use Highlight to explore their student’s needs.

“It provides a point for us as a community to come together and talk about why those things might be happening, what are our current practices, brainstorm together what might be possible interventions or solutions and then move forward with some of those ideas,” McConnell said. “It just provides a point for us to really be responsive to what our students are saying that they are experiencing and I think that’s super valuable.”

By centering student voices, we also get to support students in developing solutions that reflect how their needs should be met. Utilizing a design systems framework, Friday is developing a Student Solutions Toolkit that provides educators with a curriculum that is easy to teach, adapt and scale. This toolkit can be used in conjunction with already established student councils or newly formed student committees as a result of Highlight findings.

While some educators claim that they do or should not “see color” when they teach, students have vocalized that their “color” does indeed matter. It matters in how they experience the classroom, it matters in the instruction they receive, it matters in how they see themselves and it matters in the academic outcomes we see. If a strong sense of belonging impacts academic motivation, what did it mean for that Florida teacher’s students who could no longer look up and see reflections of leaders sharing their heritage? When we examined student responses to “My family’s culture is celebrated at my school,” Black students accounted for the highest percentage of those who “strongly or somewhat disagreed.” White students accounted for the majority of students who “strongly or somewhat disagreed” that they had the opportunity to learn about different cultures.

Highlight can be used to support necessary changes within schools, and it can serve as a tool for systemic change. When students say they do not feel safe or their school isn’t clean, we all should listen to them. Policy and decision makers have the opportunity to put student voices at the forefront and work to provide access to a quality education for every student. This is a baseline goal our society has the capacity to achieve.

Black scholars such as Mwalimu Shujaa wrote some time ago about the differences between education and schooling. He said, “the failure to take into account differing cultural orientations and unequal power relations among groups that share membership in a society is a major problem in conceptualizing school and education as overlapping processes”(Shujaa, 1993). While schooling maintains the status quo, true education has the power to transform and give possibility to a United States where future generations can live a life of sustenance and fulfillment. Education is at a crossroads, but in the words of author Arundhati Roy, we can allow the events of recent years to take us backwards, or we can allow them to be a portal making us “ready to imagine another world and ready to fight for it” with students’ voices driving us forward.

References

Arundhati Roy: ‘The pandemic is a portal’ | Free to read | Financial Times. (n.d.). Retrieved August 22, 2022, from https://www.ft.com/content/10d8f5e8-74eb-11ea-95fe-fcd274e920ca

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice Hall.

Bear, R., Kapisi, C.-O., Choate, P. W., Lindstrom, G., & Pinaki, T. ’. (2022.). Reconsidering Maslow and the hierarchy of needs from a First Nations’ perspective (Vol. 34).

Evans, G. W. (1997). The Environment of Childhood Poverty. Luthar. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.2.77

Goodenow, C. (1993). The psychological sense of school membership among adolescents: Scale development and educational correlates. Psychology in the Schools, 30(1), 79–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6807(199301)30:1<79::AID-PITS2310300113>3.0.CO;2-X

Gray, D. L. L., Hope, E. C., & Byrd, C. M. (2020). Why Black Adolescents Are Vulnerable at School and How Schools Can Provide Opportunities to Belong to Fix It. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 7(1), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732219868744

Highlight by Friday. (n.d.). Retrieved August 22, 2022, from https://friday.us/highlight/

Maslow, A.H. (1943). “A Theory of Human Motivation”. In Psychological Review, 50 (4), 430-437.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs – Research History. (n.d.). Retrieved August 22, 2022, from http://www.researchhistory.org/2012/06/16/maslows-hierarchy-of-needs/?print=1

Mattis, J. S., Simpson, N. G., Powell, W., Anderson, R. E., Kimbro, L. R., & Mattis, J. H. (2016). Positive psychology in African Americans. In E. C. Chang, C. A. Downey, J. K. Hirsch, & N. J. Lin (Eds.), Cultural, racial, and ethnic psychology book series. Positive psychology in racial and ethnic groups: Theory, research, and practice (p. 83–107). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14799-005

Nebbitt, V., Lombe, M., Pitzer, K. A., Foell, A., Enelamah, N., Chu, Y., Yu, M., Newransky, C., & Gaylord-Harden, N. (2021). Exposure to Violence and Posttraumatic Stress Among Youth in Public Housing: Do Community, Family, and Peers Matter? Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 8(1), 264–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40615-020-00780-0/FIGURES/2

P20 Motivation and Learning Lab – A University of Kentucky P20 Innovation Lab. (n.d.). Retrieved August 22, 2022, from https://motivation.uky.edu/

Public education is facing a crisis of epic proportions – The Washington Post. (n.d.). Retrieved August 22, 2022, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2022/01/30/public-education-crisis-enrollment-violence/

Shujaa, M. J. (2016). Education and Schooling: You Can Have One without the Other. Http://Dx.Doi.Org/10.1177/0042085993027004002, 27(4), 328–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085993027004002

Snyder, C. R., Shorey, H. S., Cheavens, J., Pulvers, K. M., Adams, V. H., & Wiklund, C. (2002). Hope and Academic Success in College. Undefined, 94(4), 820–826. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.94.4.820

TNTP. (2018). The Opportunity Myth: What Students Can Show Us About How School Is Letting Them Down—and How to Fix It. https://tntp.org/assets/documents/TNTP_The-Opportunity-Myth_Web.pdf

Walton, G. M., & Cohen, G. L. (2007). A Question of Belonging: Race, Social Fit, and Achievement. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.82

Whipple, S. S., Evans, G. W., Barry, R. L., & Maxwell, L. E. (2010). An ecological perspective on cumulative school and neighborhood risk factors related to achievement. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 31(6), 422–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.APPDEV.2010.07.002