Building Together: Best Practices for Equitable Neighborhood Investment

By Taylor Jones, ’23 Friday Fellow. More information about our annual summer fellowship program can be found here.

To me, neighborhoods are everything. I don’t say this solely because of the friendly faces of your neighbors, or the coffee shop a few blocks away that makes it feel like only they know what a true latte is, or the park around the corner that has been the place where you played as an elementary schooler, rebelled as a high schooler, and nostalgically revisited as an adult. I don’t say this only because a neighborhood is a place where you find friends and community, where you’re educated, or where your earliest memories occur. I say this because neighborhoods tell the story of inequity more clearly than any single person or thing ever could. I say this because I grew up in one of the most intensely segregated cities in America and saw firsthand how not only my environment, but my entire realm of possibilities shifted by simply crossing the street. Neighborhoods are the cornerstone of inequitable social outcomes in our country, and understanding how to create justice within them is the first step to creating sustainable equity everywhere.

Both history and contemporary evidence helps us understand the poorer outcomes faced by lower-income communities and communities of color. Today, despite policy interventions, 81% of America’s metropolitan areas are more racially segregated as of 2019 than they were in 1990. As a result of this stark racial separation, Black and Latino communities suffer far worse. For example, neighborhood poverty rates are highest in segregated communities of color (21%), which is three times higher than the average poverty rate in majority white neighborhoods (7%). Household incomes and homeownership rates are also significantly higher in majority white neighborhoods as opposed to communities of color.

This race-specific disparity is not surprising given America’s history of cementing structural racism by segregating neighborhoods. As Richard Rothstein makes clear in his seminal work on the history of redlining, The Color of Law, “Today’s residential segregation in the North, South, Midwest, and West is not the unintended consequence of individual choices and of otherwise well-meaning law or regulation but of unhidden public policy that explicitly segregated every metropolitan area in the United States.” The impact of redlining and other institutionalized forms of racial segregation such as blockbusting or racial covenants are responsible for much of the disparities that we see in social welfare outcomes between races at the neighborhood level. These segregation tactics also contribute to significant disparities in wealth attainment and accumulation, which are directly related to the existence of distressed neighborhoods.

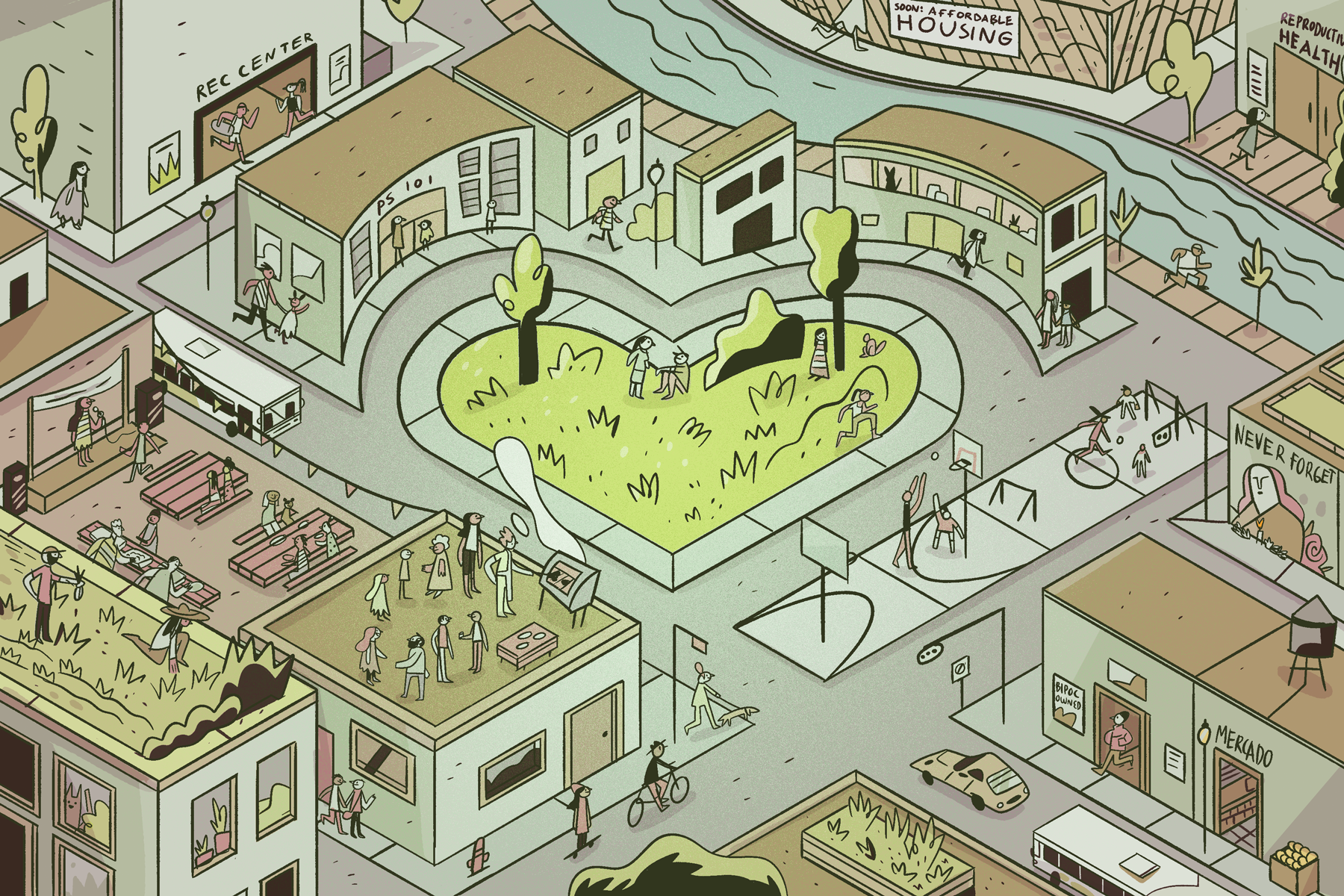

This is why understanding and investing in neighborhoods is of the utmost importance to me. Thankfully, I’m not the only one who has turned their attention to neighborhoods as key drivers for equity. For years, community developers and policymakers have made a concerted effort to build thriving communities. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development asserts that “community development activities build stronger and more resilient communities,” and they’ve earmarked millions of dollars through federal grants, namely the Community Development Block Grant Program, that support a wide range of community development activities including building affordable housing, creating recreational space, and supporting small business development.

Recently, a stronger connection has emerged between community development and righting the racial wrongs of the past. The death of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer in May of 2020, was the catalyst for wide-reaching dialogue about the systemic inequities faced by Black communities. As organizations–particularly those within the private sector–scrambled to compose plans to offset those inequities, many turned to neighborhoods as an avenue of meaningful investment. In 2020, the private sector, primarily J.P. Morgan, pledged roughly $30 billion to address racial disparities with a focus on closing the racial wealth gap, since economic gaps squarely map onto neighborhood based disparities.

While it’s exciting that there has been an influx of cash devoted to creating healthier neighborhoods for residents that are victims of historic disinvestment, it is also unwise to make investments without intentionality, especially in an environment where recent development and revitalization of a neighborhood has occurred in tandem with displacement and declining affordability.

THREE BEST PRACTICES FOR EQUITABLE COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT

There are several best practices that investors and developers can keep in mind when using neighborhood revitalization for social good, but here are three that I’ve seen be the most impactful.

Don’t Discount History

Firstly, one of the essential best practices is to thoroughly understand the history of a place. This involves delving deep into a neighborhood’s past economic, social, and environmental challenges, as well as acknowledging any historical injustices that have contributed to its current state. By fully appreciating the neighborhood’s historical context, investors can avoid repeating past mistakes and develop initiatives that are sensitive to the unique needs and aspirations of the community. As part of this, investors should be aware that redlining or other forms of residential segregation is a common experience for many places, but the details may be slightly different. Neighborhoods that have been redlined may have slightly different histories than those that experienced white flight, blockbusting, or all three. Though it may seem like this level of detail may be irrelevant due to their similar outcomes, understanding nuance allows investors to have a theory of change that is fully informed by the place or people they intend to serve instead of a catch-all approach that may not fully capture the entire story.

Learning the comprehensive history of a place can feel extremely overwhelming but the good news is that many cities and neighborhoods make information readily available. Checking out local libraries for resources, digital repositories, and connecting with community based organizations are sure fire ways to authentically familiarize yourself with a neighborhood. Additionally, organizations like Undesign the Redline, partner with community organizations to host interactive exhibits that specifically focus on how redlining impacts a particular community.

Center Residents in the Planning Processes

Secondarily, a resident-focused approach is paramount when investing in under-resourced neighborhoods. Engaging with local residents and community leaders is crucial in developing sustainable and effective solutions. Taking the time to listen and understand the concerns, aspirations, and priorities of the people living in a neighborhood allows investors to align their initiatives with the community’s interests. Empowering local residents to actively participate in the decision-making process and fostering a sense of ownership over the projects can create a more inclusive and resilient community where long-term benefits are more likely to be realized. This is also a way to stave off gentrification and attempt to ensure that investment-driven prosperity is equitably shared by long-term community members. One way to achieve this is by employing what the National Low Income Housing Coalition calls a positive development model, which is an approach that builds a new vision of community and sustainability that benefits all residents. This involves bringing different community members and stakeholder groups to the table to identify shared interests, objectives, and common struggles to ensure the development process empowers the community as a whole. The development process should enable community members to identify the types of housing, services and infrastructure that they’d like to see in their neighborhood.

Ways to invite community members to share their vision for the neighborhood can include using prompting questions like:

- Close your eyes and envision our neighborhood five years from now. What do you hope to see improved or transformed? How would these changes positively impact your daily life?

- If we could create a time capsule representing the ideal future of our neighborhood after the revitalization project, what elements would you include to showcase its success and significance?

- What are some hidden gems in your neighborhood that you believe should be preserved or enhanced during the revitalization process? Why are these places or elements so meaningful to you?

- What activities and practices should guide the relationship between the developers and community members? What norms should both parties uphold?

Prioritize Sustainability and Durability

Lastly, when making investments in under-resourced neighborhoods, a key consideration should be ensuring that initiatives are not only financially sustainable but also sufficient to address historical harm. Merely injecting money into a neighborhood without addressing past injustices can perpetuate systemic inequalities. Investors should focus on projects that not only generate economic growth but also actively seek to rectify historical disparities. This may include initiatives that provide affordable housing, access to quality education and healthcare, job training programs, and support for local small businesses. By actively working towards redressing historical harm, investors can foster more equitable and sustainable development that benefits the entire community and promotes long-lasting positive change. To take things a step further, these investments should appreciate the magnitude of the issue. If investors are truly interested in narrowing disparities that are millions of dollars in scope, their investments should reflect that and be equally substantial.

Though the complexity of mitigating historical harm and building thriving neighborhoods for all is great, these practices can encourage, direct, and sustain future investments in a way that is meaningful, resident-centric and equitable.